LYNCHING MEMORIAL: Volunteer calls on Limestone to claim its history

Published 6:45 am Thursday, April 26, 2018

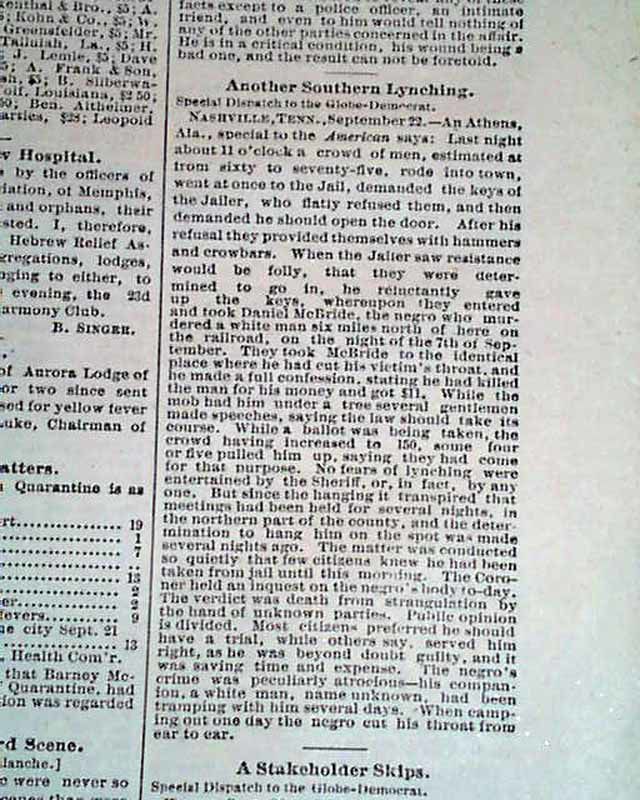

- An article from the Sept. 28, 1878, edition of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat recounts the lynching of Daniel McBride, who was pulled from jail and hanged in front of a crowd of about 150 people, six miles north of Athens. The coroner at the time ruled the death "strangulation by unknown parties."

Madeline Burkhardt will tell you she’s always appreciated history. The daughter of an Athens State University library director, she maintained her enthusiasm for the subject throughout her years at Athens High School and her college years at Auburn University.

However, she said, it took moving to Montgomery to realize there was a large chunk of history that was overlooked.

Trending

“This part of history isn’t taught in school,” she said. “That’s not anything against our teachers, because they do a wonderful job at what they do, but the textbooks they’re given and the requirements from the state of Alabama don’t touch on this very much because it’s such a dark part of history.”

The dark part is lynching.

More than 4,400 African-Americans were lynched between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Initiative. More than 300 of them took place in Alabama.

“Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials,” the EJI website reads. “Unlike the hangings of white people and outlaws in communities where there were no functioning criminal justice system, racial terror lynchings in the American South were acts of violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order.”

EJI released a report on lynching in America in 2015. In the years since, EJI has worked to memorialize this part of history by visiting lynching sites, creating public markers and even collecting soil.

Burkhardt found out about the project through her work as the adult education coordinator and curator at the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery. She said the organizations work “pretty closely” together, and when she learned about the project, she knew she had to volunteer.

Trending

“You don’t hear about the violence and the social injustice that occurred (during that time period),” she said, “and when you do hear that, hopefully it sparks something within you.”

Among other tasks, she filled an empty jar with soil from the Limestone County site where Daniel McBride was lynched in 1878. A St. Louis Globe-Democrat article described the incident, saying a group of 60–75 men rode into town and demanded the keys to the jail where McBride was being held for allegedly robbing and murdering a man he had been traveling with.

According to the article, they removed McBride from the jail and took him out to the spot where his alleged victim died, six miles north of Athens.

“While a ballot was being taken, the crowd having increased to 150, some four or five pulled him up, saying they had come for that purpose,” the article reads, adding that even the sheriff had joined the group. The article goes on to say several people had met repeatedly in the days leading up to the murder to plan the lynching, and the coroner at the time ruled the death “strangulation by unknown parties.”

For Burkhardt, the event strikes a personal chord. She knows that as a white person with family history in Athens and Limestone County, it’s possible members of her family were involved, even as spectators in the crowd.

“There’s a very good chance that my ancestors participated in the lynching of Daniel McBride,” she said. “It was 150 people.”

“You have to own up to that at some point,” she added. “You have to want to change things. It’s not equal treatment, and you can’t justify it using the Bible or other words like some people do.”

The soil she collected has been split between two new institutions opening today, including the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which will be the nation’s first memorial of its kind dedicated to lynching.

Set on six acres, the memorial features more than 800 rectangular slabs of steel in varying shades of brown — one for each of the United States counties where researchers identified lynchings. Each pillar stands 6 feet tall and includes the names and death dates of those who were lynched.

The pillars are suspended from the ceiling to evoke the image of a hanged brown body. Identical monuments are laid out like coffins around the memorial. EJI encourages counties to claim their respective monument and install it in the county as part of their own memorial.

Those left unclaimed will remain displayed for visitors.

“If they don’t claim their coffin, millions of people are going to notice that,” Burkhardt said.

Limestone County’s column features three names — McBride, who died Sept. 21, 1878; Joe Harris, who died June 16, 1901; and Alex MacDonald, who died Dec. 27, 1905. Burkhardt said she reached out to Athens Mayor Ronnie Marks and Athens Communications Specialist Holly Hollman about arranging a way for Limestone County to claim its coffin.

She also planned to speak with Limestone County Commissioner Mark Yarbrough.

“There are people who don’t even know that it happened in their county,” Burkhardt said. “They need to own up to that history and talk about it instead of having a white narrative of history.”

Burkhardt said prior to her move to Montgomery, she was unaware of other narratives. She admitted she comes from a place of privilege, “where I never really had to deal with this.”

“When I moved here to Montgomery, I started talking to other people who were involved in other things and seeing what really happened,” Burkhardt said.

She wants to make sure the people of Limestone County aren’t also overlooking this part of their history.

“Y’all need to know you have a pillar down here,” she said. “You need to come get it.”