Preserving history: Fulton talks Trinity history

Published 11:00 am Sunday, March 29, 2015

- Local author Charlotte Fulton talks about her new book about Trinity School in Athens.

Charlotte Fulton has spent her career making past events tangible to those not there to see them for themselves, both as a reporter and, now, as an historical author.

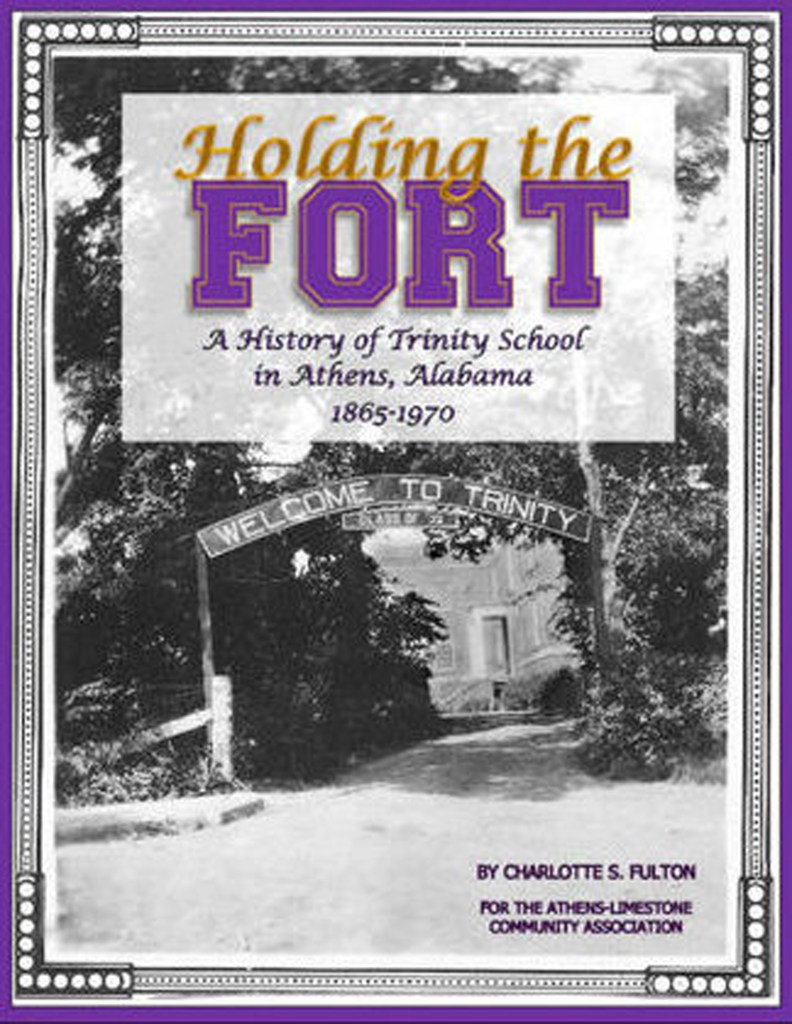

Fulton’s book, “Holding the Fort,” shares her extensive research into Trinity High School and the people who made it memorable. She presented an overview of her research Thursday night at a book-signing event at Athens-Limestone Public Library to raise money for the Trinity-Fort Henderson Project.

The school began at the onset of Reconstruction when a northern Baptist missionary named Mary Fletcher Wells, who had been caring for wounded Union soldiers in Athens, decided she wanted to provide education to freed slaves.

She opened the school with the help of the American Missionary Association in a home in Athens that has since been moved to Greenbrier. Fulton said she thought it was “very exciting” that the building where the story starts is still standing today.

During Reconstruction, communities across the South wanted the American Missionary Association to build schools and send them teachers. So many wanted schools and teachers, Fulton said, that the organization was considering shuttering Wells’ school and sending her somewhere else. The school she started had become dilapidated and was declared unfit to inhabit.

The black community reached out to Trinity Congregational Church pastor Horace Taylor and asked him to intervene on their behalf to keep Wells in Athens if the community would make its own bricks and provide the materials to build the school.

The missionary association replied, “Let them arise and build.”

Thus was born the Trinity School Society and the building was completed in 1882. Trinity school flourished and became the heart of the black community, Fulton said. The school burned to the ground in 1907, but moved to the Fort Henderson property the next year. This time, a residence was built for the staff and named Wells Cottage, in honor of Mary Wells, who died in 1892.

The school burned again in 1913 and was rebuilt once more before it became a public school in the 1940s, when it was moved into its current location on Browns Ferry Street.

Trinity was closed for good in 1970, after federal courts ordered the desegregation of public schools. What remains is a shell of memories, but Fulton said the “Trinity spirit” remains unbroken. That’s why she wrote the book, she said.

“It was just so interesting,” she said. “Everyone had a different story and they were all so compelling. All of that just made me very curious to find out what this was.”

Sales of her book will go toward the restoration and preservation of the Trinity site. Plans are for it to become a community center and local black history museum.