Historian shares some Fort Henderson history

Published 8:00 am Thursday, August 15, 2019

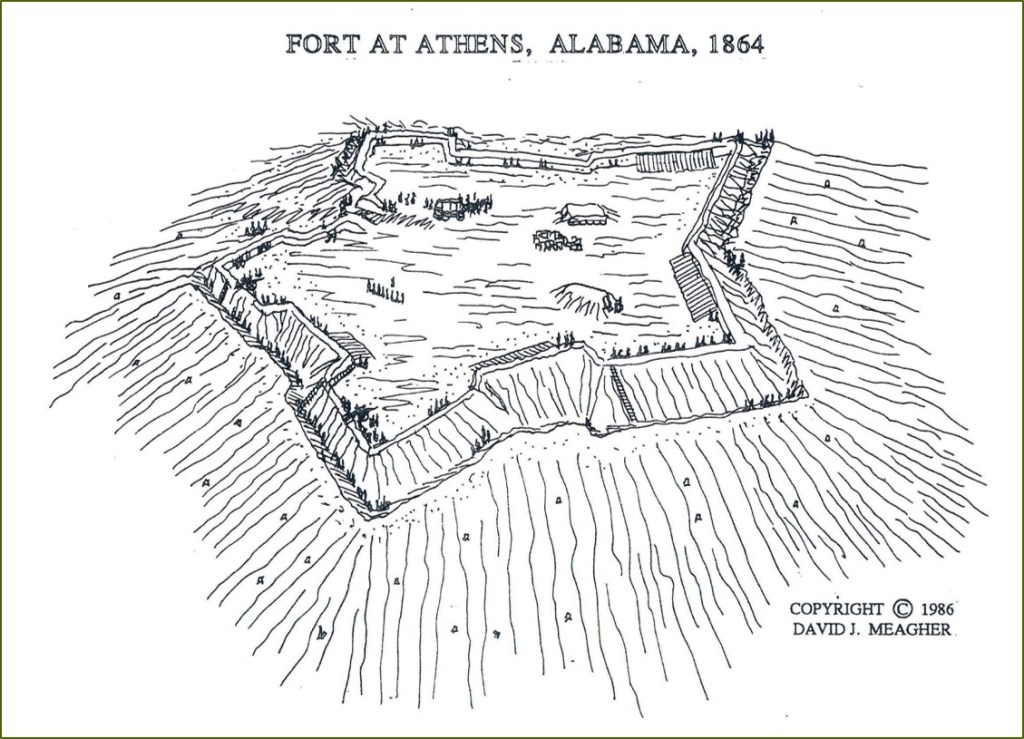

- This is a depiction of Fort Henderson by artist David Meagher.

Historian Daniel Davis said he’s learned two things over the years.

First, he believes any day on a battlefield is better than a day in the office. He and other members of the community recently had the opportunity to visit the Civil War battlefield at Fort Henderson in Athens.

Second, he’s learned history always happens in the shade.

“So, if you are outside on a tour, always stand in the shade,” he said.

Davis, an education associate with American Battlefield Trust, a nonprofit organization that preserves America’s hallowed battlegrounds, works to educate the public about what happened in history and why it matters.

Davis, who lives with his wife in Fredericksburg, Virginia, worked for five years as a historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park and at Appomattox Court House National Historic site.

Now, he is working on behalf of American Battlefield Trust to research the history of Fort Henderson and the people who fought there, according to Limestone County Archivist Rebekah Davis.

Daniel Davis is working with the Athens-Limestone Community Association to help write, design and fabricate the interpretive signs the ALCA will erect along the perimeter of the former fort so visitors can walk through the story, Rebekah Davis said.

ABT is paying to have the signs created. It is also working with the University of Alabama and the ALCA to designate a conservation easement on the Trinity-Fort Henderson Complex to prevent development that would be detrimental to the historic area.

While Davis was in Athens on his recent visit, he spoke to members of the Athens Rotary Club about some of the history surrounding Fort Henderson. Much of his discussion was about African-American soldiers, who were either from Athens and Limestone County or enlisted in the area, and the 110th United States Colored Infantry Regiment at Fort Henderson.

110th United States Colored Infantry Regiment

“Unfortunately, no one has been able to locate a photograph of the men from the 110th in uniform during the war,” Davis said.

However, it is known that the 110th was formed in late 1863 or early 1864, Davis said.

Their primary mission was to man the blockhouses and protect the railroad and the garrisons between Decatur and Nashville, he said.

“One of those fortifications is here in Athens, obviously,” Davis said, referring to Fort Henderson.

The fort was built in the spring of 1862. By the fall of 1864, it was garrisoned under the command of Col. Wallace Campbell and it housed three units, including the 110th.

On Sept. 20, 1864, Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest received word to launch a raid from Mississippi eastward into Alabama as a way to break up a supply route to William Tecumseh Sherman’s army in Georgia.

“Athens ends up being one of Forrest’s main targets,” Davis said.

On Sept. 24, 1864, Confederate forces surrounded the garrison at Fort Henderson, and Forrest convinced Campbell he was outnumbered. Campbell surrendered.

Davis said the largest contingent from three units stationed at Fort Henderson was the 110th. Over the last few months, Davis has worked with Rebekah Davis and Peggy Towns to research the unit, but he said they have only “scratched the surface.”

He said Campbell surrendered roughly 233 enlisted men from the 110th. After going through service records, Davis and the others determined 145 of those men were either born in Limestone County or enlisted in the county. Davis and the others reviewed pension records at the National Archives and discovered 65 of the 145 men filed pensions or had pension filed on their behalves. He explained how after the war if a soldier applied for a pension and it was returned for more information or other reasons, and the Department of Interior didn’t hear back in a certain amount of time, some of those records were destroyed.

“The stories of some of these soldiers are incredibly interesting, but at the same time very tragic,” Davis said.

The soldiers

He said the youngest soldier to enlist was 17 and the oldest was 45, while the average age of a soldier was 25. Davis said many of the men enlisted for three years, so after the war was over they were returned to Union control.

“They still had a good year left on their service,” he said.

Davis said many of the enlisted men were former slaves, and some were born as far away as Virginia, North Carolina and Maryland. Others were local to Alabama and Mississippi, he said.

Moses Peete

The eldest was a man named Moses Peete, 45. He was married to a woman in Limestone County.

After being captured at Fort Henderson, he was taken to Mobile and later returned to Union control.

Davis said Peete was sent out on the Alabama River on a steamer known as The Natchez. While lowering a water bucket into the river and pulling it back up, a wave hit the boat and knocked him over. He drowned and his body was never recovered, Davis said.

Peete’s wife remained in Limestone County with her children.

Julius and Samuel Redus

Davis also spoke of a pair of brothers known as Julius and Samuel Redus. He discovered the brothers were slaves on a plantation owned by Thomas Redus. After being captured at Fort Henderson, captivity took a toll on the brothers, Davis said. Samuel died in the National Hospital on June 24, 1865, and Julius, who was on his way to Nashville to rejoin his unit, died in Mississippi two days later.

Isaac Townsend

Another soldier was Isaac Townsend, who survived the war and returned to Athens, Davis said. When Townsend died in July 1919, the Limestone Negro Undertaker Co. sought reimbursement from the Department of Interior for the $180 burial fee. From what Davis could tell from Townsend’s file, the bill was never paid.

George Allen

Davis also spoke of George Allen, who had at least 12 children who could be identified through his pension file. Allen returned to Athens after his service to purchase a parcel of land from his former owner, Davis said. He died in May 1896.

Doctor Peete

Doctor Peete also served in the unit, Davis said. When he was born, Peete suffered from complications and was taken to the local “sawbones,” or doctor, who rehabilitated him. As a result, Peete was given the name “Doctor Peete.”

Davis said Doctor Peete had an affinity for Army life. After the war, he enlisted in the 38th United States Infantry and was mustered in at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. He was stationed in Kansas, where his main duty was protecting the stage lines running from Kansas to Denver.

Doctor Peete left the service in 1870, but he didn’t return to Limestone County. He married a woman in Dallas, where he later died.

John Roberts

Davis said one of the most interesting soldiers he came across was John Roberts. His file wasn’t found by the national archivist but rather in St. Louis. He was born near Belle Mina on March 18, 1838, to Nathan and Millie Roberts. Davis said they know he had siblings because his nephew signed his death certificate.

After the war, Roberts came back to Athens and Limestone County and married three times. At some point, Roberts bought 79 acres in Jefferson County. In 1911, he bought a parcel of land for more than $1,600 from a Jack Grisham. Davis said they couldn’t figure out how Roberts was able to pay so much for a parcel of land.

“More than likely, he was a very successful farmer,” Davis said.

The most interesting thing about Roberts is that he died May 19, 1943, in Athens at age 105, Davis said. A copy of his original death certificate was in his file.

“He is the oldest we have so far been able to locate from the 110th United States Colored Troops,” Davis said.

Roberts’ file was the last Davis looked at and he felt it was the perfect ending to that stage in his research.

“Think about people like Doctor Peete, John Roberts, Moses Peete,” Davis said. “When I stop and think about these men, one thing comes to mind. These African-American soldiers didn’t know each other. They were separated by generations. But, they stood on one another’s shoulders. The same goes for us today. We stand on their shoulders as Americans and what they fought for to help establish and maintain the United States.”