(Column) Local media is struggling. Government subsidies would make it worse.

Published 9:15 am Saturday, February 24, 2024

It is an axiom and an accusation: Journalists consider the phrase “good news” an oxymoron. There is a short slide from “We don’t report the planes that land safely” to a generally jaundiced view of things, which makes consuming journalism akin to eating spinach — virtuous, but more a duty than a delight.

Technology — radio, then television, then satellites, the internet and social media — has vastly expanded the menu of choices of news sources. Simultaneously, some journalistic practices, including the conflation of everything with politics, have forfeited the public’s trust in, and appetite for, journalism.

A steady stream of bad economic news about the newspaper business has elicited some supposedly ameliorative ideas. Many, however, illustrate another axiom: Some improvements can make matters worse.

Time, Newsweek and Sports Illustrated are shadows of their former selves; “cord cutting” and streaming are transforming television news. Most stunning, however, is the collapse of the newspaper culture. The annual report from Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism says:

- Since 2005, nearly 2,900 newspapers have closed, eliminating the jobs of two-thirds (43,000) of newspaper journalists.

- In 2023, an average of five papers disappeared every two weeks.

- More than half of the nation’s counties (1,766 of 3,143) are “news deserts,” having either no local news source, or just one, typically a weekly newspaper.

- A large majority of the 6,000 remaining newspapers are weeklies.

- Newspapers’ Washington bureaus are vanishing: Most states have no journalist reporting from the seat of the federal government.

In Illinois, probably the worst-governed state (see: out migration, economic growth, tax burden, unfunded pensions, K-12 education results, etc.), the State Journal-Register in the capital, Springfield, in 2000 had 70 people in its newsroom. Now, Jon K. Lauck says, it has fewer than 10 reporters and editors, “including two sports reporters and a photographer.” A historian at the University of South Dakota, Lauck is editor in chief of Middle West Review, in which he reports: Since 2015, the Omaha World-Herald’s newsroom has contracted from more than 200 to 62, with more cuts coming. The paper’s Sunday circulation, 302,000 in 1980, is now about 40,000. Figures for the Indianapolis Star, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Detroit Free Press, Kansas City Star, Chicago Tribune, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and others are comparable.

And even worse for some smaller papers: The St. Cloud, Minn., paper, which once had 36 employees in its newsroom, now has three.

The common economic problem is the migration, for reasonable economic calculations, of advertising dollars to digital platforms. The Illinois Local Journalism Task Force proposes making local news organizations wards of government by subsidizing them with direct grants, providing subsidies for low-income subscribers, giving tax exemptions and tax credits for news organizations (also for subscribers and advertisers and for hiring reporters), and mandating government advertising in the news outlets.

What could go wrong? Everything.

Soon, government would mandate hiring and coverage quotas for “underrepresented” groups, would enforce government’s idea of editorial “balance,” would censor what government considers “misinformation” about public health, diversity, equity and inclusion, and would dictate all things pertinent to government’s ever-lengthening agenda. The task force’s recommendations — journalism throwing itself into government’s muscular arms — are a recipe for making local news sources as admired and trusted as government is.

The Roman Empire is gone, as are the Carolingian, Byzantine, Ottoman, Habsburg, Spanish, Portuguese, British, French and Soviet empires. Newspapers need not be eternal. They need not, however, despair about improvising new ways to present fresh material that readers are willing to pay for. At least if they are not force-fed journalists’ politics.

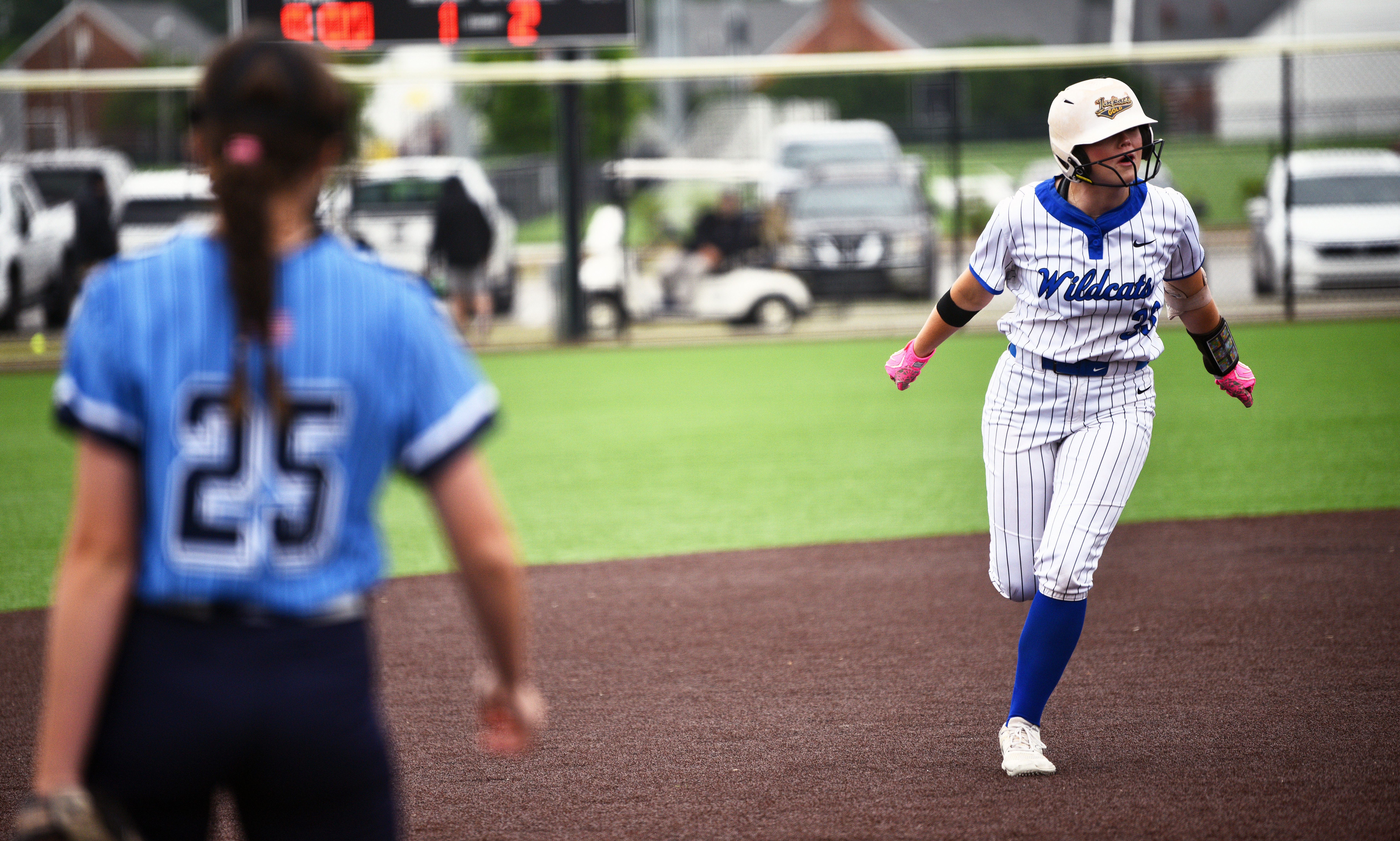

Many Americans have wholesome habits they acquired as youngsters delivering newspapers. After school, they folded 50 or more of that day’s edition of the local paper into squares that were easy to toss from a rolling bicycle onto neighborhood porches. Dispensed from a canvas bag attached to the handlebars of balloon-tire Schwinns, the papers kept the community abreast of Little League box scores (children’s names in agate type: a sip of celebrity) and the possibility that a traffic light might be installed at the intersection of Elm and Green streets.

The collapse of trust in journalists (a recent Gallup and Knight Foundation survey found that just 19 percent of Americans term their trust “high” or “very high,” down nine points in four years) is less severe regarding local news sources. This might have something to do with the absence of a political slant to those box scores or to reports concerning that traffic light.