There and back again: Coxey veteran turns 100 surrounded by family, friends

Published 5:58 pm Friday, September 8, 2023

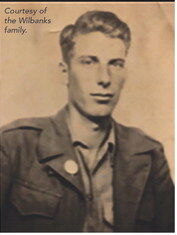

- Aaron Wilbanks’s service photo.

For his 100th birthday, a special celebration was held at the Sheriff ’s Rodeo Arena for World War II veteran Aaron Wilbanks of Coxey. Surrounded by his four children, other family and friends, Wilbanks enjoyed seeing everyone after staying at home for so long due to the pandemic.

Wilbanks was born in the Coxey community on Sep. 6, 1923, and was the oldest of six children —three boys and three girls. He grew up farming and went to school at Clements. When he turned 19 years old, he was drafted into military service.

Trending

“They come got me when they wanted me and they kept me until they got through with me,” he said. “In January 1943, I went into the Army.”

Wilbanks reported to Ft. McClellan and then to Camp McPherson in Atlanta, Ga. He was assigned to the 35th Division, 216th Field Artillery Battalion, Battery A.

“The big guns! 105s … the shells weighed 33 pounds!” he said.

From Atlanta, Wilbanks was sent to San Luis Obispo in California for three months, to Fort Rucker for three months, to Tennessee on maneuvers for three months, and then to Camp Butner in North Carolina for more training. Once training was complete, they headed to Camp Kilmer in New Jersey where they boarded a ship for England.

“We got all our shots, our G.I. haircut, and our combat clothes. We got on the boat and left for Liverpool, England. It was the flagship of the convoy. There was boats all around us and you’d go this way six minutes and turn and go that way for six minutes. I stayed on that boat for 27 days,” Wilbanks said.

Once in Liverpool, Wilbanks hopped the train for Okehampton in England where they stayed for two several weeks before heading for Omaha Beach in Normandy, France. On July 4,1944, the troops were served a large meal and Wilbanks knew it was because for many, it would be their last.

Trending

As part of the Third Army, the 216th Field Artillery Battalion followed General George C. Patton.

“He spearheaded just about all of the big ones,” Wilbanks said.

“From the time we was in England, we were getting ready for France. We went to France in July. The invasion was in June,” he recalled. “All our trucks, we had them where they’d run underwater. We landed on Omaha Beach. We crossed the English Chanel on July 5. Across it was about 80 miles and we crossed it at night. Rough, rough, rough … talk about rough in that little ole boat. Seasick! It was the only time I ever got seasick.”

They waited until the tide was coming out and sat the boat on the bottom. The front of the boat was let down and the troops drove out. Once the tide came back, the boat would leave for another load.

“When we drove off, it was blowing mines and don’t let anyone ever tell you they weren’t scared to death. That’s when your heart was up in your mouth. That was our first — drove off the boat and hit land in France. The invasion was about 30 days but they hadn’t went nowhere. They made it about four or five miles from the beach but we were within shooting range because we could shoot seven miles but three miles was about the most we ever shot,” Wilbanks said.

He continued, “I told them where the shell hit and if it went over 100 foot, I’d tell them and usually it took about three shells to hit the target but when you hit the target, you’d do it with one gun. When you hitthe target, you’d call all of them in then.”

From Omaha Beach they went into Normandy, France to Saint Lo- Battle of the Hedgerows.

“They were dug in and I mean DUG IN. We blowed and blowed and blowed and blowed and couldn’t get them out. We just couldn’t blow them out so they shut the guns down all day long one day and they bombed them. The bomber would come over and unload, go back to England and reload, and come back and bomb them all day long. It got ‘em running then. From there on, we was fighting. From there until the war ended. It got to where you couldn’t sleep if you couldn’t hear the gun shooting,” Wilbanks said.

He said, “We weren’t around no kitchen. We carried our eats in a bag most of the time. It was c-rations in a can and chocolate bars and stuff like that. We had to eat it out of the can and we would eat when we got hungry when we had a chance. A chocolate bar might be all we had for a meal. There wasn’t no breakfast, dinner, and supper.”

“A lot of times, we would get out there and kill us a calf and take it to the kitchen and cook it. That wasn’t legal, now. We’d take chickens, rabbits, and things like that. It was a lot of boys in there that cook,” he said.

Sometimes Wilbanks would receive a package from home and his mother would send him cakes.

“There would be something in there that reminded you of home. Cotton bolls, they’d put that in they’re just about all the time. Of course, they didn’t have any idea what was going on over there,” he said.

They made their way through France and into Belgium and the Battle of the Bulge. The 216th cleared the town of Bastogne. Wilbanks said that although he can still picture it, it’s hard to tell others how it happened.

“The Bulge didn’t last long. Germany pulled everything they had and put everything together and that was the last breath they had. They was on the run! They were running and that was the last push they made,” he said. “When we got the word that the war was over, we turned on a generator they had left behind and lit the place up. We got to see daylight at dark!”

Wilbanks was about 40 miles from Berlin when the war was over in May and he had logged more than 1,600 miles. After patrolling the area, the 216th headed to England to board the Queen Mary for home on September 5, 1945 — the day before his 22nd birthday. “The mess hall on the Queen Mary was the swimming pool,” he smiled. “The 35th Division was President Truman’s division in World War I and when we pulled into New York, he was there. The whole 35th Division was on the Queen Mary, about 15,000 of us.” Wilbanks had enough points to have a discharge and didn’t have to leave for the Pacific. He said that once they were back in the United States, he took the train to Georgia and the bus home to Limestone County. His family knew he was coming home but they didn’t know when so he surprised them.

Wilbanks was awarded several medals including The Bronze Star but stressed that he wasn’t there for the medals but to serve his country. After the war, he went to Detroit for about a year but came back home. He farmed and took a job at Redstone Arsenal in 1950. He married Christine Green, with whom he grew up, and they raised four children in the Coxey community. Christine passed away in 2014 after 62 years of marriage. Wilbanks continued to work his farm until recently and still rakes hay from time to time and his children all live within five minutes so he is rarely alone.

“All I have to do these days is wash dishes,” he said.