Yesterday and today: Lincoln’s life comes alive in new novel, ‘The Rail Splitter, by John Cribb

Published 12:00 am Thursday, February 9, 2023

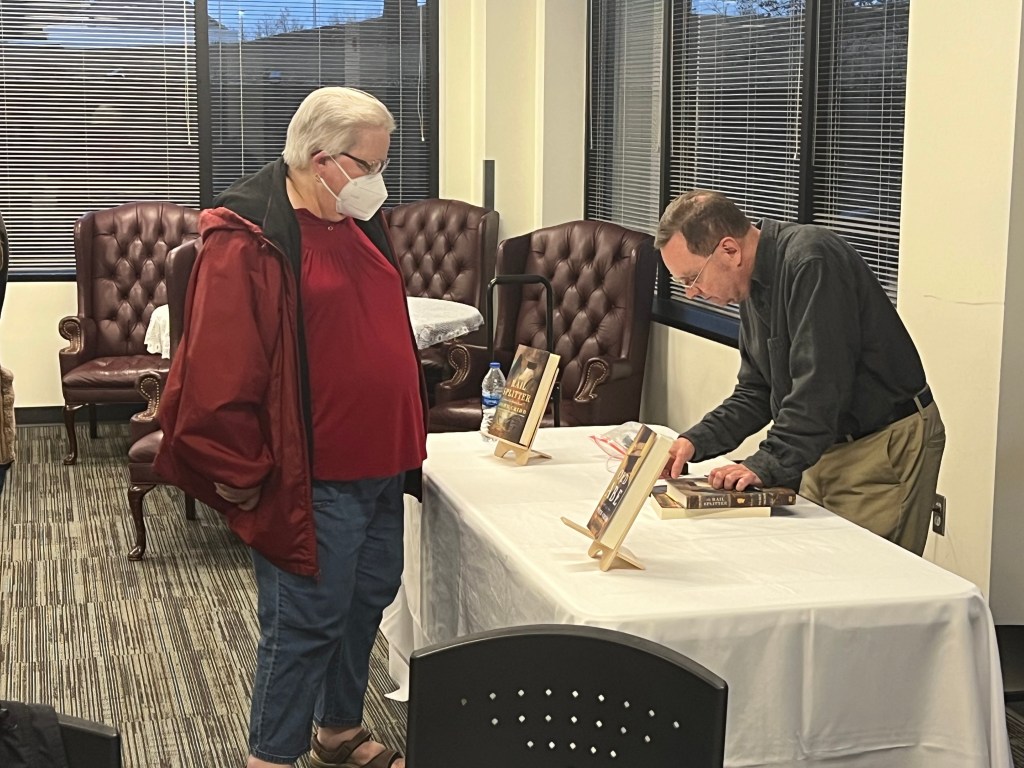

- Author John Cribb signs copies of his new novel about Abraham Lincoln, 'The Rail Splitter,' Feb. 2 at Pell City Library.

Before ‘Old Abe’ was old, he was a young man building on the virtues that would one day position him as the 16th president of the United States. And although he had less than a single year total of formal schooling, the success of Abraham Lincoln’s life presents us still with a consummate model for personal and public service and behavior, according to author John Cribb.

Few are the Lincoln scholars who are as studied and familiar with Lincoln’s life and work as is Cribb. Fewer still are the nuanced and researched fictionalized works about the self-taught man who would write some of America’s preeminent works of history — the Gettysburg Address and Emancipation Proclamation among those — but Cribb has done this. First, in his book, “Old Abe,” published in 2020 and detailing Lincoln’s presidency, and now in “The Rail Splitter” (Republic Book Publishers), giving us the life of Lincoln through his early years to the cusp of his presidential nomination.

While thousands of nonfiction books have been written about Lincoln, there is a scarcity of novelizations that draw on deep research, treating a fictional subject with the rigorous exploration of a doctoral thesis, Cribb said during a Feb. 3 presentation at Pell City Library. It is this literary hole the author is attempting to fill, and for a specific reason, he said: to make the life of Lincoln not only accessible, but imitable, to everyone.

“I wrote both of these books as historical novels to really try to bring Lincoln alive,” Cribb said. “To make him a walking, talking, breathing fellow, not just that stiff image we know on the five dollar bill. Fiction can do that in a way that nonfiction can’t. But (at the same time), I really wanted to make it a very accurate reading of his life.”

Such accuracy written with a narrative flair not only makes Lincoln approachable, but whether in his books or lecture, Cribb tells the story of Abraham Lincoln as if talking about an old friend he has known since childhood.

“You’re with him every page as he splits his rails, sails down the river, his marriage, involvement with politics and rise on a national stage,” Cribb said about “The Rail Splitter.” “That story ends in late 1859, and then ‘Old Abe’ picks up in May 1860, when he’s about to be nominated. Then you’re with him for all the big, iconic events of this life, like the Gettysburg Address, the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.”

But beyond those iconic moments, most interesting for Cribb is how Lincoln, born in a log cabin on the frontier with limited access to formal education, rose to become the man he was.

His research, he said, has identified several key virtues that help to both explain Lincoln’s success and still reverberate throughout society.

“I’m going to zero in on five aspects of his life, five keys to success for him,” Cribb said during the St. Clair County presentation. “(Five aspects) that still hold lessons for all of us today.”

“Key No. 1, and this is really no surprise to us because it’s an old-fashioned virtue: It’s just work, hard work,” Cribb said. ”This is something you learned while growing up on the frontier where (if you didn’t work) you weren’t going to survive.

“Lincoln wrote that his father put an axe into his hand when he was 8 years old, and until he was 23 he was almost constantly handling that axe, doing all kinds of things.”

Things such as “splitting thousands and thousands of rails out on the frontier. … He’s put out so many rails, that when he ran for president in 1860,” Cribb said, “the Republican Party nicknamed him the ‘rail-splitter candidate’ to show he was a man of the people.”

But many people work hard, Cribb said. What Lincoln also learned from a self-sufficient early life was self-reliance, the second key to making the man.

“If you wanted to stay warm, you split your own (logs) and your own firewood,” Cribb said. “The 16th president of the United States knew how to do all kinds of things. So, he could slaughter a hog, he could clean a gun, he could build a boat.”

But that didn’t mean a life of isolation, Cribb said.

“I say self-reliance (is the virtue), and he did have a strong sense of self-reliance,” Cribb said. “But that doesn’t mean he did it all himself. Nobody does — right? Nobody goes through life doing everything themselves. We all rely on others, family, friends, community.”

Vital for this to Lincoln was his marriage to Mary Todd Lincoln and the belief she had in her husband.

“She said, ‘He’s going to be president someday,’” said Cribb. “She saw it. She believed it. … (That’s) important here: There were times in Lincoln’s life, like for everybody, (when) inertia sets in a little bit and you need some pushing and prodding — and she was there to push and prod. She really believed in him and was very ambitious. You could probably make the case, if you wanted to, that he would not have been the president of the United States had it not been for Mary.”

Such driving ambition on the part of both Lincolns is how Cribb described the third virtue.

“Lincoln is really good at stepping up to challenges and seizing opportunities when they come along,” Cribb said. “This is where he gets into politics.”

But he wouldn’t have gotten far, Cribb said, had he not exemplified the fourth virtue: An eagerness to learn.

Although his institutionalized learning “added up to less than a year in school … he loved learning, he loved reading. He used to say, ‘my best friend is a man who can get me a book,’ and you know, books were hard to come out on the frontier. He would literally walk miles through the woods to lay his hands on a book if he could get one when he was living in that little frontier village in New Salem, Ill.

This was the early 1830s, and already Lincoln was showing himself to be a leader by example, Cribb said.

“Years later, people of New Salem remembered seeing Lincoln on logs or fences or tree stumps, or just walking along with with one of these books, his head just buried, studying away until he turns himself into an attorney. Until he’s able to be admitted to the bar and is eventually a very successful and very good attorney.”

Such an education would do him a great service throughout his presidency, and especially during the Civil War, Cribb said.

“When Lincoln gets to where he’s elected president, he gets to Washington and right away the country falls into war, just within days, and Lincoln really quickly realizes that he hadn’t learned too much about fighting a war, much less overseeing a war effort,” Cribb said. “And one of the things he does is … is he checks out a bunch of books at the Library of Congress on how to fight a war.

“Lincoln is brilliant at learning on the job. That’s one reason he was such a great president — he’s really, really great at learning on the job.”

But all of these virtues wouldn’t have made Lincoln the president he was without a fifth, his Northstar: A concept of freedom.

“Lincoln is fiercely devoted to the idea of freedom,” Cribb said. “He knows it’s allowed him to rise in the world. He also knows that the world had been waiting for centuries for a place like the United States … founded on the idea that people should be able to live in freedom, and that the issue of slavery was directly opposite to what this country is supposed to be.

“Lincoln knows that if slavery is allowed to get out of the South, this great American experiment in freedom is going to be snuffed out, and that is going to dash the hopes of millions of people here and around the world. The eyes of the world were on the United States. Lincoln knew exactly what the stakes were.”

Which makes it “amazing,” said one commentator from the Pell City audience during Cribb’s presentation, “how some people still don’t accept his concepts. Isn’t it amazing how people are still fighting about that concept? Not only in the United States, but around the world?”

Cribb agreed, and noted how prescient Lincoln was in his writing.

“It is up to every generation to struggle to uphold those principles of freedom and equality,” Cribb said in citing information from the Gettysburg Address. “It’s an ongoing struggle.”