Local resident works to ID unknown soldiers

Published 3:00 am Saturday, January 11, 2020

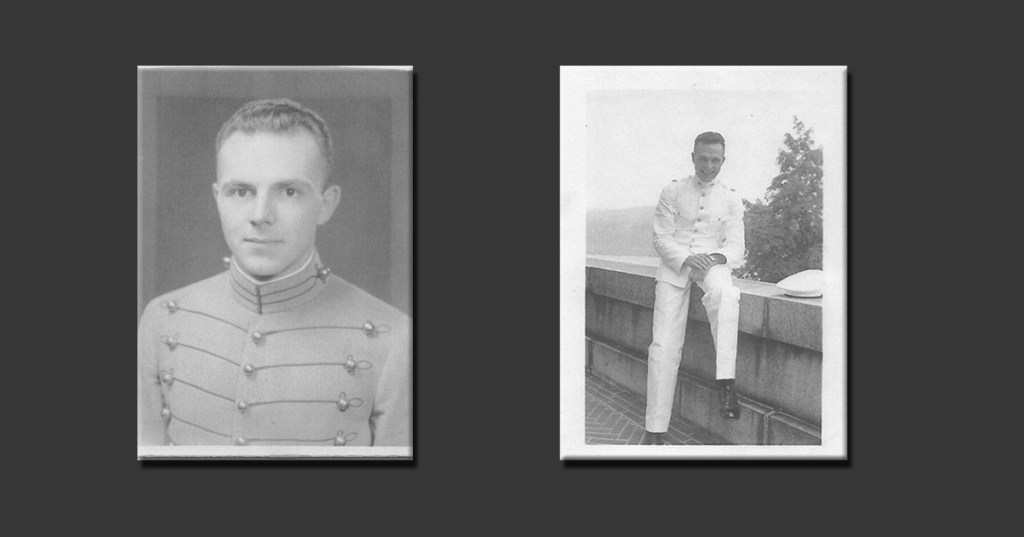

- Capt. Donald Snoke died in World War II as a prisoner of war and was buried in a large grave marked "Unknowns" in Hawaii. Decades later, his cousin, Erich Snoke, wants the opportunity to positively identify Donald's remains, along with some of the hundreds of others buried with him.

Most folks can tell you where their relatives are buried. Some can point you to the marker where their relative’s name can be found in the cemetery.

But what if learning a relative existed came with learning they were buried with hundreds of others marked “Unknowns” on an island in the Pacific Ocean?

That was the case for Erich Snoke, an Air Force veteran and genealogy enthusiast who decided eight years ago to learn more about a mystery cousin on his father’s side of the family. He determined the cousin, Donald R. Snoke, was an Army captain who went missing in action in Taiwan.

“I was trying to find out what he was doing there,” Erich Snoke said. “… I thought, well, maybe he was a pilot or something, but when I found out he was in the artillery, I started to do a bit more research.”

Snoke learned his cousin had been captured in 1942 by Japanese forces. After three years as a prisoner of war, the captain was loaded with more than a thousand others onto a Japanese ship headed from the Philippines to Japan.

“That ship was attacked from aircraft … and sunk in the Philippines,” Snoke said. “There were maybe 100 prisoners that were killed during the attack. The survivors swam to shore and were rounded up again by the Japanese.”

From there, they were loaded onto two more ships, but the harbor was attacked again, killing Snoke’s cousin and more than 400 other prisoners. The remains of 431 people were located after the war, Snoke said, but only a handful were positively identified by personal effects or dental records.

The rest ended up in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii. Decades later, Snoke would find the cousin’s name on a list of people allegedly buried in one of multiple mass graves at the site. While his cousin was from Pennsylvania, Snoke found 15 other names on the list belonging to Alabamians.

“It was kind of exciting to find (my cousin’s) name,” Snoke said. “The disappointing thing is I know where he’s buried but his remains are yet to be identified because the only way they can identify now is through DNA analysis.”

Because the remains of hundreds of individuals were buried together in a single grave, the Department of Defense requires evidence that at least 60% of the service members can be identified before starting the process. That means family members for at least 60% of those on the list have to be willing to provide a DNA sample and permission for their relative to be disinterred.

“Last I knew, they had about 34%,” Snoke said.

To help get that other 26%, Snoke said he’s tried tracking down some of the families. He maintains a Facebook page called “Enoura Maru – Hellship” where relatives can post photos of those who were killed on the same ship as his cousin. Snoke also uses genealogy sites like Ancestry.com to find possible relatives.

He said he’s gotten a few responses from people who think the dead should be left to rest in peace. Others are hesitant to provide DNA samples to a government agency, but he’s also connected with some who are grateful for the opportunity to find closure.

“We’re just kind of inching along there to reach that 60% threshold,” Snoke said.

However, this is a search that has gone on for eight years, and Snoke admits there are times when it gets to be too much.

“I do get discouraged,” Snoke said, but he added those are the times when he’s grateful for help from people like his friend, local author John Davis. “When I get discouraged, he picks up the banner and does things like contact (the local newspaper). He’s written congressmen and senators as well.”

Snoke and Davis previously worked together on a mission to have a U.S. stamp in honor of Limestone Judge James E. Horton Jr., who famously set aside the guilty verdict of one of the Scottsboro Boys, nine black boys who were accused of raping two white women on a train in 1931. Snoke and Davis haven’t gotten the stamp yet, but they did help drum up the interest that led to the Athens Post Office being renamed the Judge James E. Horton Jr. Post Office Building.

Snoke’s approach to the identification endeavor isn’t much different. He wants the opportunity to properly identify his cousin, but he said even if he doesn’t find his cousin among the 431, maybe he can help others find their cousins or siblings or grandparents.