AN ABILITY: Rifle maker, artist overcomes adversity

Published 6:45 am Tuesday, November 5, 2019

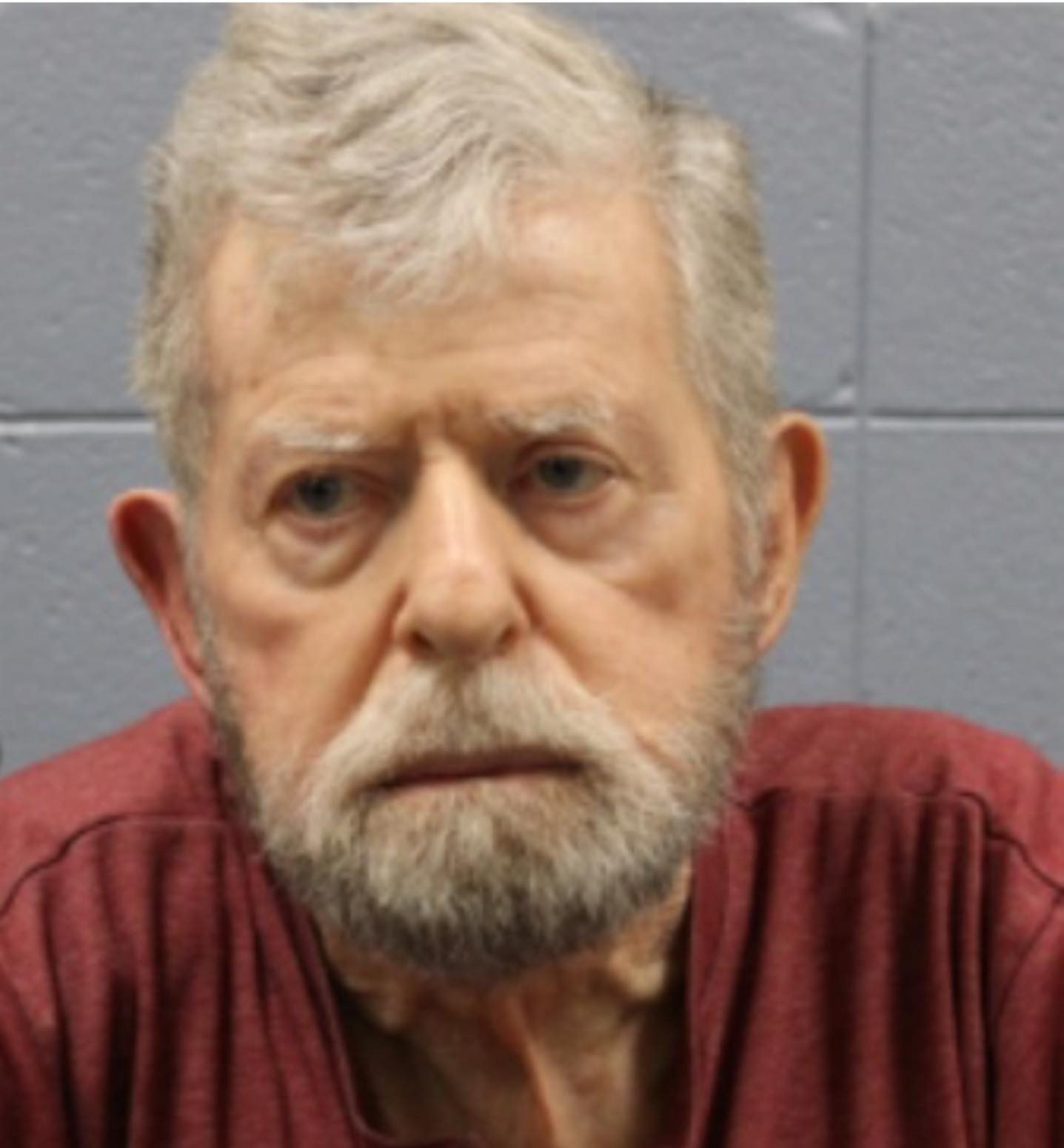

- Greg S. Murry, a rifle maker and metal artist, speaks to the Athens Rotary Club Friday in front of some of his art and hand-built rifles.

Life for Greg S. Murry hasn’t been easy.

Though the rifle maker and metal artist comes from a long line of pioneers, artists, authors, inventors and entrepreneurs, he wasn’t given much of chance as a child.

Trending

Murry and his wife, Pat, were in Athens Friday to talk rifle-making with members of the Athens Rotary Club, but Murry also spoke about overcoming adversity and finding his niche.

“I’m dyslexic,” Murry told the crowd as he stood behind a table of his handcrafted works.

As a young boy, he couldn’t read and remembers the hurt he felt when he was compared to other children in the family.

“It was a very deep, troubling point in my life,” he said.

Looking back, Murry doesn’t believe he was the only one in his lineage with dyslexia.

On Murry’s mother’s side, members of the Griswold family were among the first colonists of Connecticut. His great-great-grandfather Victor Moreau Griswold wrote the book, “Hugo Blanc the Artist.”

Trending

His uncle, Ed Lowe, invented kitty litter.

As an adult, Murry said he could see “the earmarks of dyslexia” in their lives. Yet as a child, it was something Murry made great efforts to keep hidden.

“I was always the first to wake up in the morning and I was always the first to go to sleep,” he said. “If I could go to sleep before everyone else, I could hide from my inabilities. If I could wake up first in the morning, I could get my fly rod, fishing pole, BB gun, traps or whatever and go down to the river and live in the woods. I could hide in God’s creation and get myself back together.”

In the seventh grade, Murry’s world came tumbling down. His struggles were brought out in the open and given a name.

“It is a phrase we don’t use anymore around our children, and that phrase is retarded,” Murry said.

“In the seventh grade, I was diagnosed as retarded.”

Murry said he was bullied and brutalized by his peers.

As a teenager, he hid even deeper. Instead of hiding in the woods, he started hiding in bottles of alcohol and drugs.

“I hated school,” he said. “I graduated when I was 20 years old with a 1.0 grade average.”

He said he failed every class in junior high. In high school, he had one teacher who gave him a chance.

The English teacher started a photography club, and Murry got involved. That was the first time he realized he had something inside him worth pursuing.

“I’m saying all of this because we probably all know someone who is dyslexic,” Murry said. “Some of you might be dyslexic. We might have grandchildren, we might have cousins, we might have friends who are dyslexic, and we can see the struggle. Give them great encouragement. Give them something they can grab on to, so they can feel worth something.”

After high school, Murry continued pursuing photography before starting in the horse business. He worked with hunters, jumpers and thoroughbreds. He traveled all over the country.

“In the horse business, you could get in a whole lot trouble,” he said. “I definitely got into a whole lot of trouble.”

He got out of the horse business for a time and into the printing trade. He apprenticed for three years before he got in more trouble and lost that job.

It was then some friends approached Murry and told him to get out of his hometown.

So Murry uprooted his family and moved to Dallas.

“I was in pursuit of changing my life,” Murry said, adding Dallas did help him find some direction.

Later, the family moved to Tennessee, where Murry worked at some high-end horse farms and a polo estate.

Muzzle loading rifles

Murry managed the polo estate for 10 years. During that time, a friend turned him on to the muzzle-loading rifle world. Murry’s son was 9 years old, and they went to his friend’s farm to shoot a flintlock rifle. His son loved it, so the Murrys started having discussions about getting him one for Christmas.

Murry called some rifle makers and discovered the prices were too high. Most of them were booked up, too.

Murry said he wondered if he had a talent he didn’t know about. He bought some tools, got some parts and built his first rifle for his 9-year-old boy.

“It turned out pretty darn good,” Murry said.

He said his employer at the time saw the rifle and wanted one, too. So Murry built another rifle.

“He loved it,” Murry said.

Turns out, that person was friends with a CEO at the Coca-Cola Company, who also wanted a rifle.

After building the third rifle, Murry said, a friend came to him and said, “Greg, you’ve had a terrible, terrible, tough life, and there is obviously something inside you that you didn’t know you had.”

Murry said the friend laid money down on the table and told him, “I want you to really concentrate, and I want you to build the best work you can build.”

When Murry delivered the musket to his friend, who was the nephew of a well-known historian in the muzzle loading world, his life started to change, he said.

Murry took the rifle to his friend’s uncle and after a long conversation, Murry said the man told him if he believed in reincarnation, he’d believe Murry was a reincarnated famous rifle maker.

Later on, another conversation with the same man gave Murry an “a-ha moment.”

“Here was this dyslexic kid that was going nowhere, this adult that didn’t have any faith in himself, who finally had something,” Murry said. “That apple from the tree that didn’t fall far from my family. From all the gene pool of art, inventing, entrepreneurs, people colonizing America, it all handed down to me, and now, here I am, making fine flintlock rifles.”

Crockett Long Rifle

As Murry’s career as a rifle maker grew, he ended up in Leiper’s Fort, Tennessee. It was there he had a brick-and-mortar shop for seven years.

The self-taught rifle maker was creating award-winning, high-end rifles and becoming a renowned engraver. It wasn’t long before Murry was introduced to a descendant of the Crockett family.

“She inherited a Crockett rifle made in Tennessee,” Murry said.

Through four conversations, Murry tried to talk the woman into letting him see it, but he said she didn’t want anyone to see it.

“It is a very historic rifle, and I was hoping I could get my eyes on it so I could recreate it,” Murry said.

He figured it would never happen.

However, 14 years later, Murry got a phone call. He was told the woman had died and a member of her family had inherited the rifle. The family wanted to continue conversations with Murry because they understood the historic significance of the rifle.

“We would like you to restore it, and we would like for you to tell us something about it,” Murry was told.

After seeing the rifle and doing some research, Murry discovered it was made by the Crockett rifle-making family that is connected to the legendary frontiersman Davy Crockett.

Murry said the rifle is signed “S&AC,” which stands for Samuel and Andrew Crockett III. Samuel and Andrew Crockett III are the son and grandson of Lt. Andrew Crockett, who is well-known for making rifles, Murry said. David “Davy” Crockett is their cousin, he said.

The Crocketts made the rifle at the Forge Seat Rifle Shop, which operated from 1808-1826.

Crockett rifles are connected to several battles, including the battle of King’s Mountain and the Battle of New Orleans. Only three rifles from the forge have survived.

Murry was commissioned by the family to create seven reproductions for the Crockett descendants. He has delivered 15 Crockett Long Rifle reproductions in all.

The reproductions take 200 bench hours to create, Murry said, and each is made of cherry wood like the original. The Crockett Long Rifle has a $9,000 price tag.

Today, Murry lives in Columbia, Tennessee, and works from home. He continues to make flintlock rifles and pistols as well as metal art.

The self-taught craftsman gives his glory to God. He said his faith is what grounded him. He signs each of his pieces “To Jesus Christ Be The Glory” or “TJCBTG.”

His wife believes his life is now a testament of what a person can do regardless of what they are told.

Visit www.crockettlongrifle.com to find out more about Murry and the Crockett Long Rifle.