Gladys Black: A love that survived the grave

Published 11:55 am Wednesday, November 29, 2017

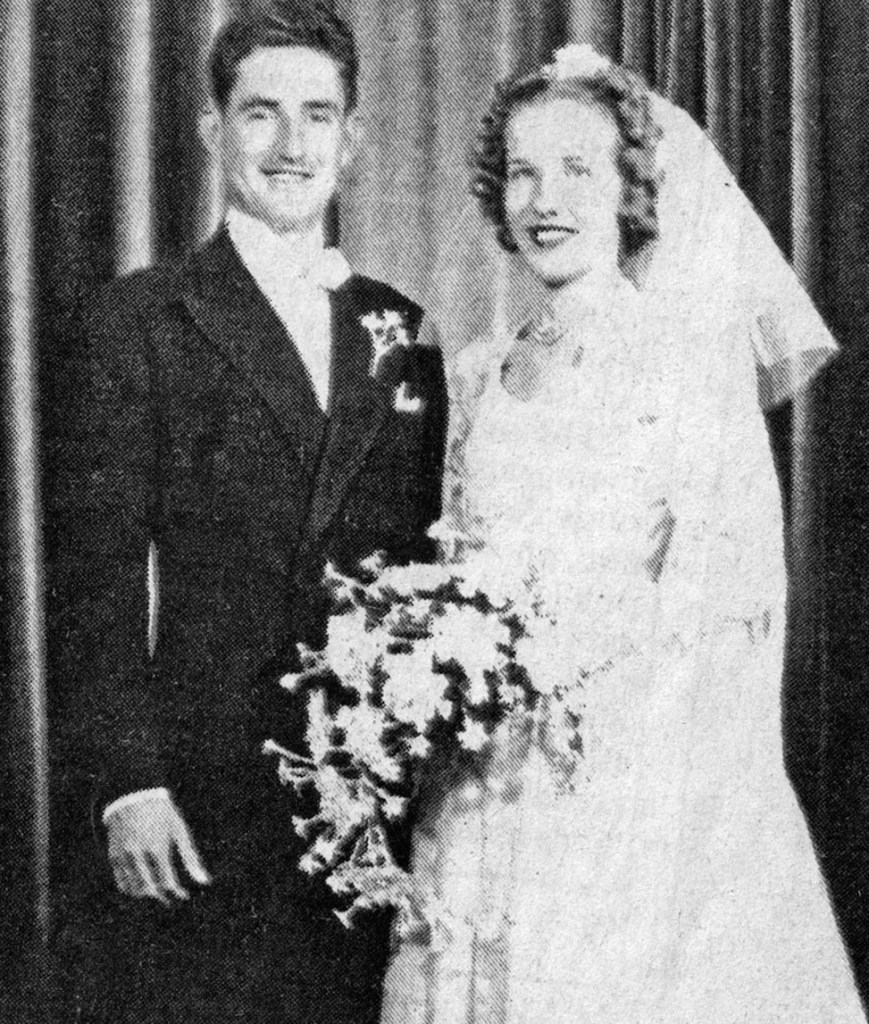

- Kenneth and Gladys Black on their wedding day Nov. 10, 1946. Kenny died in 2002, ending a 56-year marriage. Gladys died on Nov. 14, 2017, at 92.

Gladys Bonislawski, 16, of Chelsea, Massachusetts, was already a beautiful girl when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack set her on an unlikely path to Athens, Alabama.

The Bonislawskis were a patriotic family — and for good reason. Her father had immigrated to America from Poland and earned his citizenship by fighting Germans in WWI.

Trending

Kenneth Black, 20, of Athens, was having a late breakfast at a restaurant when the music was interrupted by an announcement that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. The date that will live in infamy set him on an unlikely path to Chelsea.

He had not lived an easy life. When he was 13, his father died, leaving a widow and three children. Kenny quit high school in 1937 and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps in Athens to help support his family. He earned $30 a month, $25 of which went to his mother. His older brother was a Marine, and when the recruiter came to Athens, Kenny tried to enlist but was turned away for being too skinny.

But he was set on being a Marine.

In August 1942, he hitchhiked to Decatur and was accepted in the Marines. Early the following Monday, Kenny dressed in his best, a spanking new bluish-green suit and a pair of white Crosby shoes, boarded a Greyhound and headed off to war. He dressed up because: “I was going off to fight for my country and wanted to look my best.” After nine weeks of boot camp at Paris Island, South Carolina, he went to New River, South Carolina, and was assigned to a machine gun squad in the newly formed 4th Marine Division, 25th Regiment.

At New River, a fellow Marine showed Kenny a photo of Gladys Bonislawski, the Marine’s cousin and a striking blonde. Kenny liked what he saw and wrote her a letter. She replied that she was “writing to several men in service” and enclosed a photo. One more won’t make much difference, Kenny thought, and put the picture in his wallet.

In July 1943, he sailed to Camp Pendleton, near San Diego, via the Panama Canal. Soon, the tiny Pacific Islands that he’d never heard of, with obscure names like Roi-Namur, Saipan and Tinian would become synonymous with American bravery and the fighting spirit of the U.S. Marines.

Trending

The battle for Roi-Namur was short and bloody. The Marines killed 3,472 Japanese and captured 264. Marine losses were 190 killed and 547 wounded.

Kenny was unscathed.

The next target was Saipan, only 1,485 miles from Tokyo, where an estimated 30,000 Japanese were ready to die for their Emperor. After 25 days of fighting, Old Glory was hoisted atop a Japanese telephone pole. The 4th Division had suffered 5,981 killed, wounded and missing. The Japanese toll was far worse: 23,811 known dead and 810 taken prisoner.

Kenny was unscathed.

Tinian Island was next. It was there that Kenny’s outfit was overrun by a Banzai charge. A Japanese soldier jumped into Kenny’s foxhole, and he killed him with his bare hands, rolling his body out of the foxhole. He rested back on his elbows and gasped for air and looked up. A Japanese bayonetted him in the gut and left him for dead.

Kenny, his lung almost collapsed and diaphragm punctured, woke that night aboard ship. He was carried to a hospital in New Hebrides. His weight dropped to 112 – a loss of 50 pounds – and he couldn’t do an “about face” when he was awarded a Purple Heart. Later, he was transferred to a hospital in Rhode Island. It was there that Gladys Bonislawski, who had written to him on Saipan, paid him a visit.

After Kenny was discharged from the Marines in 1945, he moved to Chester, Massachusetts, to help his older brother with commercial painting. He called Gladys for a date, and she took him out for steak. Neither had a car. They courted by telephone and weekend dates. They married on the Marine Corps Birthday – November 10, 1946. Gladys was 21, Kenny 25.

He didn’t have enough money to buy a diamond ring. Gladys opted instead for a wide wedding band. They had a big wedding but no money and no car. They received enough cash gifts to catch a train to Athens, where they lived with Black’s mother for a year and a half, then rented a small apartment on East Street. Kenny attended Athens College on the GI Bill. Gladys later said she was one of two strangers in Athens and couldn’t get a job.

“They couldn’t understand me.”

So, she designed book cases, and Kenny built them. In 1947, they had saved $240 and bought a 1937 Plymouth. Finally, nine years later, they saved enough to buy a house. Gladys got a job at Redstone Arsenal, and Kenny worked for the Alabama Department of Revenue.

They bought mail-order furniture that had to be assembled. They didn’t have children but always had a dog. They travelled widely, and Kenny seldom missed a 4th Marine Reunion. They were always together.

“I love that man,” Gladys told me. Her man died on Oct. 29, 2002, ending a 56-year marriage.

Gladys had a beautiful display case constructed to display Kenny’s Marine uniform, along with other memorabilia that can be seen at the Alabama Veterans Museum.

Gladys died on Nov. 14, 2017, at 92 and was buried next to her Marine in Athens Cemetery. She and Kenny were from a generation of giants. They endured the Great Depression, fought a war that saved western democracy, then rebuilt a better world for my generation. May their deeds live forever in the hearts of free people.

— Barksdale, a retired attorney, author and historian, is an occasional contributor to The News Courier. He can be reached at jbarks2013@gmail.com.