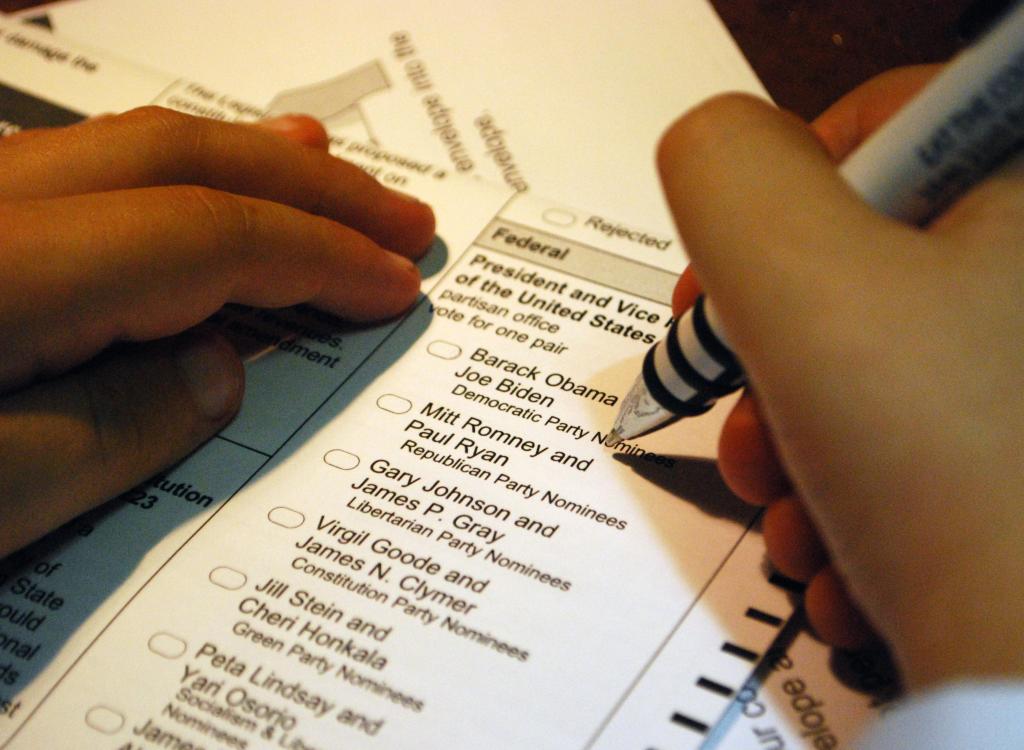

Ballot-booth selfies: A threat to secret voting?

Published 6:00 am Tuesday, August 25, 2015

- Ballot-booth selfies: A threat to secret voting?

In the age of the omnipresent cellphone and the proliferation of social media, it might seem a fool’s errand for government to try to ban the selfie.

In New Hampshire, a federal judge recently said it is also unconstitutional.

The selfie in question is something called the ballot selfie. The Granite State in 2014 amended state law to prohibit voters from taking photos of their marked ballots “and distributing or sharing the image via social media or by any other means.”

The state said it was protecting the sanctity of the secret ballot and guarding against vote-buying or voter coercion. The latter two could be aided by a person producing evidence of how he or she voted.

But opponents said the prohibition was a violation of free-speech rights. After that fall’s Republican primary, it was challenged by:

— Leon Rideout, a state representative who posted his ballot to show he had voted for himself and other Republican candidates and encouraged others to do the same.

— Brandon Ross, who took a photo of his ballot to memorialize his statehouse candidacy and posted it — along with the message “Come at me, bro” — only after learning the attorney general’s office was attempting to prosecute people for violating the ban.

— Andrew Langlois, who wrote in the name of his recently deceased dog, Akira, for the office of U.S. senator. He took a photo and posted it on Facebook to illustrate his point that “all of the candidates SUCK.”

Selfies — yes, selfies — just won a big political and legal victory.

The American Civil Liberties Union of New Hampshire took up their cause and won. U.S. District Judge Paul Barbadoro said in a 42-page decision that the state had violated the First Amendment in providing a solution for a problem that doesn’t exist.

The record “does not include any evidence that either vote buying or voter coercion has occurred in New Hampshire since the late 1800s,” Barbadoro wrote.

He added: “Few if any rights are more vital to a well-functioning democracy than either the right to speak out on political issues or the right to vote free from coercion and improper influence. But the record in this case simply will not support a claim that these two interests are in irreconcilable conflict.”

The ACLU’s state legal director, Gilles Bissonnette, said the state doesn’t have to wait for a problem to manifest itself before taking action. But none of the three plaintiffs whom New Hampshire was preparing to prosecute were accused of vote-buying or coercion.

The state’s broad ban, Bissonnette said, “sweeps within its scope protected innocent speech,” such as Langlois’s protest.

New Hampshire plans to appeal the ruling.

Barbadoro’s opinion relies partly on a Supreme Court decision that is only weeks old but is already causing problems for government regulation of speech. The court’s decision in Reed v. Town of Gilbertstruck down an Arizona municipality’s sign regulations, which put stricter limits on signs with directions to church gatherings than on those with other types of messages, such as advertisements for political candidates.

The majority opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas greatly expanded the kind of government regulation that is considered to be content-based and thus subject to a court’s highest review, called “strict scrutiny.” Strict scrutiny requires government to prove that a restriction on speech “furthers a compelling interest and is narrowly tailored to achieve that interest,” Thomas wrote.

As Barbadoro interpreted Reed: “A law that is content-based on its face will be subject to strict scrutiny even though it does not favor one viewpoint over another and regardless of whether the legislature acted with benign motivations when it adopted the law.”

Laws rarely survive such a review, and Reed already has been cited by courts in striking down a panhandling law and a prohibition on robo-calls.

Barbadoro’s decision has also sparked a lively discussion about the wisdom of banning ballot selfies.

Richard Hasen, a prolific election law expert at the University of California at Irvine, wrote an op-ed for Reuters that called ballot selfies a “threat to democracy” that could revitalize the practice of selling votes and encourage “potential coercion from employers, union bosses and others.”

Others disagree, saying any kind of vote-selling scheme would be much more easily accomplished with absentee ballots.

Michael McDonald, an election law expert at the University of Florida, said verifying that someone voted a certain way by having them post proof on social media “would be easily detected.”

“As a way of stealing an election, this doesn’t seem a very effective method,” he said in an interview.

Moreover, anyone dumb enough to try it, McDonald said, would probably add a message: “I just made 20 bucks.”

Although New Hampshire was the first state to specifically ban ballot selfies on social media, punishable by a fine of up to $1,000, many states have long-standing bans on photography in polling places.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, some are questioning whether the rise of cellphone cameras and influence of social media requires a new look at their practices. Utah passed a law that explicitly allows ballot selfies.

McDonald found out about Florida’s regulations when he had the notion that a selfie of him voting would make a good Twitter avatar. But precinct officials nixed that. He had to retreat the requisite distance from the polling place before he could take the shot.

Except for the “I voted” sticker on his lapel, it’s hard to discern what he’s up to.