Decoration Day, a Southern tradition, helps keep memories, respect alive

Published 10:15 pm Saturday, August 19, 2006

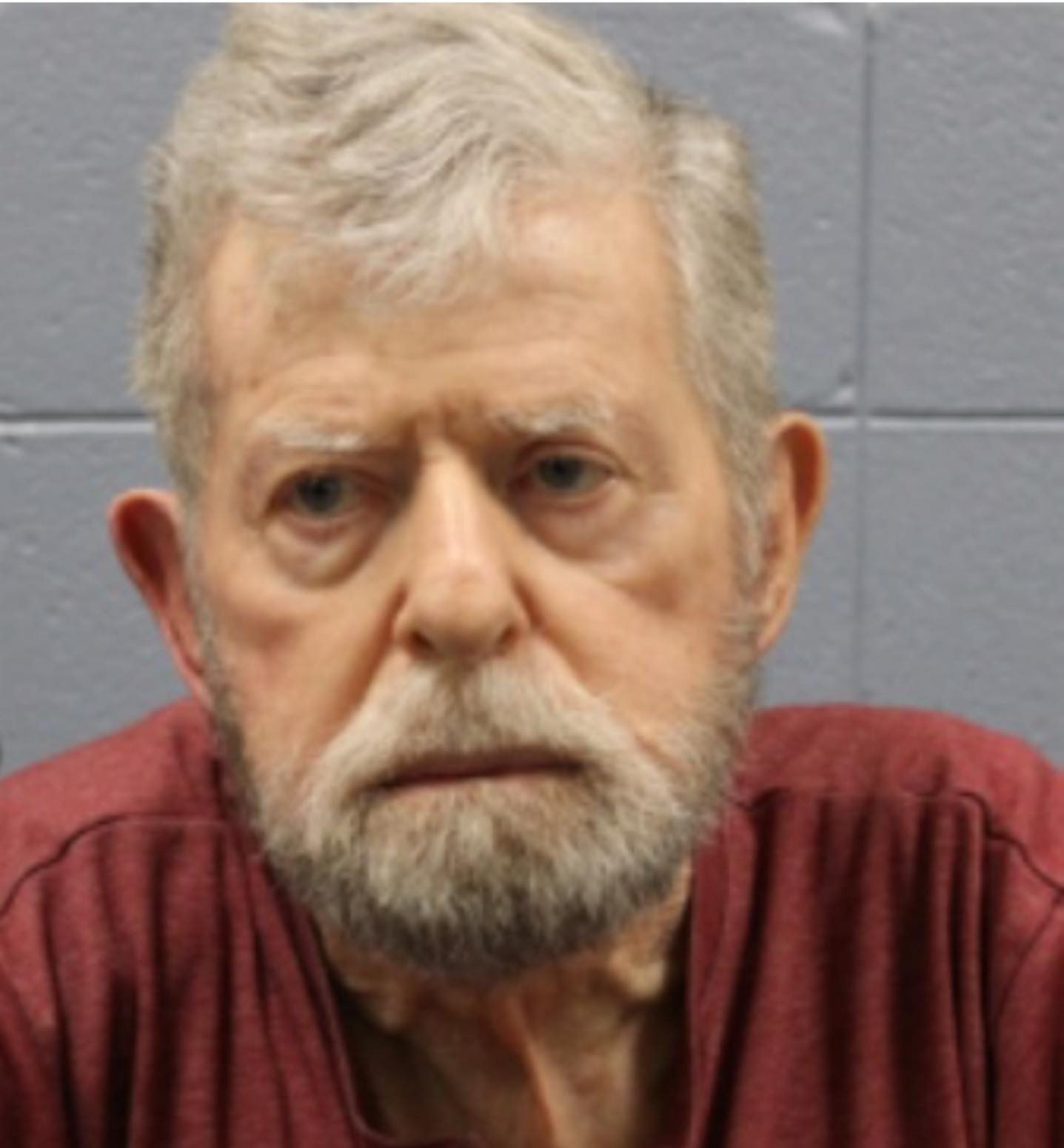

Walter Romine, 88, a widower for 13 years and father of a son long since grown, keeps company mostly with the dead.

He knows most of them by name, and can give their location to anyone who comes asking.

It’s company he’s accustomed to, having helped maintain Higgins Cemetery in northwestern Limestone County for most of his life, beginning when he was a teen, then resuming when he moved nearby 52 years ago. The dead don’t make demands, but Romine feels a responsibility to ensure this final resting place is serene and neat, as close to heaven as he can make it.

“This is my living now,” he said, having retired 20 years ago from carpentry work and 18 years at Flanagan Lumber Co. in Athens. “I live to help around here.”

On Saturday, he placed two large arrangements of orange silk flowers on the grave of Birtie A. Romine, his wife who died in 1993 at age 73.

He is at the cemetery for the annual Decoration Day, a Southern tradition that has its roots in honoring the Civil War dead but branched into a day of care and fund-raising for the rural burying grounds that would otherwise be lost to the whims of weather, kudzu, and families that no longer live and die within a mile of one another.

Families of the more than 400 souls buried here come from Athens, Rogersville, Anderson and across the Tennessee line to honor their dead with bunches of silk flowers arranged at the crafts store on U.S. Highway 72, or by family members with a knack for it. The same is occurring at two other local cemeteries today, Sandlin and Myers, carrying on a ritual that begins each May and continues into September at cemeteries across the county and the South.

Higgins Cemetery, started sometime in the 1800s (the oldest stone on which writing is legible is dated 1855) by the Higgins family and is not linked to any church or funeral home. It offers free plots and few restrictions, and a volunteer committee that rights overturned vases or statues after a storm and keeps the grass from creeping over loved ones.

People aren’t allowed to lay claim to a plot before death, but most respect that H.C. Bates should have the space next to his late wife, or that the plot next to Elizabeth Miller, who was only 26 when she died, should be left for her parents. Southerners don’t forget courtesy, even in grief.

The acre of graves is alive with color — petals of silk and plastic; pinwheels of red, white and blue; angels of concrete and marble.

Decoration for this cemetery does not mean a perfectly uniform sprig of daffodils, that will fade but never die, placed in a vase above a flat marker like those in modern cemeteries. Here, decoration can be anything a person can imagine, whatever might honor the memory of the dead or bring a sense of peace to those left behind.

In recent years, many of those who come bearing flowers and respect are middle aged or older. Those charged with preserving these burying grounds aren’t sure if the responsibility for caring for the dead will come with maturity, or if the tradition will meet the same fate of those it honors.

“We need some young people here,” Romine said. “I’m gettin’ too old.”

Phillip Reyer, Limestone County’s archivist, does not believe the tradition is in danger.

“I don’t think it will die out. It’s too ingrained,” he said.

Evolving tradition

In Limestone County’s earliest settlements, when farms stretched as far as the eye could see, people buried their dead in a seemingly endless supply of land.

“They buried them on family land,” Reyer said. “Usually, they’d start out just as family cemeteries, but as time went on, other people in the community would also bury their dead in that cemetery. It would become a community cemetery.”

As farms grew smaller and families moved or died, many of Limestone’s smaller family burying grounds were lost amid weeds and bramble until they were unearthed by developers or farmers.

“In the early days, a lot of them couldn’t afford to have tombstones,” Reyer said. “In this county, there’d be quite large cemeteries with only a handful of stones.”

Reyer said the majority of cemeteries in Limestone County are small, rural graveyards where people honor the dead as they see fit.

“The decoration is an offering to the dead — you are giving a gift —and it doesn’t really matter what it is,” he said. “Now, you see these tombstones that have balloons on them, sometimes stuffed animals, or little statues.”

Reyer said Decoration Day is not a tradition in all areas of the South, but he is not sure which states recognize the special day.

“Some people think it’s just very bizarre that we do that,” he said.

Decoration Day was once the phrase used for what it now Memorial Day, initially created as a time to honor the nation’s Civil War dead by decorating their graves.

That tradition was renamed Memorial Day and was first widely observed on May 30, 1868.

In the southeast, the tradition of grave memorials soon evolved to include decorating the graves of loved ones or ancestors long buried but remembered in stories told on front porches. Until about 10 years ago, Decoration Day was typically celebrated sometime in May as a reunion of scattered families who came for “dinner on the ground,” with cloths spread across folding tables or boards balanced on stacks of concrete blocks.

The picnics were especially common at cemeteries adjoining the small, white, wooden churches that dot the region. Cars would overflow gravel lots and families would pile out — the women and children laboring under the weight of Tupperware containers and casserole dishes marked with pieces of masking tape bearing the owners’ names, the men carrying folding chairs and tools for cleaning graves.

After gravesites were neat and clean, families would gather for prayer, pot-luck and tales of those whose bodies had been placed in the graves but who were brought alive again, briefly, to join the picnic.

Organizing picnics became too much effort for families in which parents both work and children’s weekends were filled with ballgames and recitals. For a few years, the committee at Higgins Cemetery tried offering chicken stew to feed the volunteers and raise money, but that, too, was not worth the expense and effort, said Faye Chandler, a member of the Higgins Cemetery committee whose parents, grandparents and sister are buried there.

Saturday, Chandler and Opal Britton sat at a folding card table under a canopy, accepting greetings and wrinkled tens and twenties, which were placed in a cardboard cigar box and recorded in a spiral notebook. For another year, the cemetery committee should have enough to pay someone to mow.

If a storm comes, Chandler and her husband and son come to cut felled trees or repair any damage, she said. The family lives less than a tenth of a mile from the cemetery.

“Everything done at the cemetery is volunteer by people around here, except for the mowing,” she said. “We just like for it to look nice.”

Romine said the cemetery was overgrown at one point but was cleared by his family and others. About eight years ago, Chandler said, the families installed a fence and began working to keep the grounds neat.

“It’s a community thing,” she said.

A special place

Kay Miller comes to the annual Decoration Day at Higgins Cemetery to ensure the graves of her daughter, two sisters, grandfathers and other family members look nice.

Her eyes mist as she tries to describe why she comes. “It’s just a day to honor them,” she says.

She also gives a donation for upkeep. “It’s well worth it,” she said. “If something blows off and they don’t know whose grave it belongs to, they hang it on the fence so you can find it.”

Bessie Yocum of Rogersville places memorials on graves of siblings who died before she was born and one, Trudie Chambers, whose life ended in 1931 at age 8.

“I barely remember her,” she said.

H.C. Bates came to give his wife and parents bouquets. He has also given some of his land to expand the cemetery. He donated an acre, and James Griffin donated another half acre, more than doubling the cemetery’s size.

Bates has been coming here since 1963, when his father was buried.

“It’s tradition,” he said. “They want to recognize the dead.”

Walter Romine, ambling through the stones in his overalls, boots and trucker’s cap, says he is closer to his own end than anyone else in the community.

“I’m about the oldest one around,” he said. He stood still among the headstones, thinking his body will someday lie here.

“We ain’t never ready, are we?”

He hopes tradition will bring a new generation of people to Decoration Day, people who will care for his grave as lovingly as he has cared for generations of the dead.